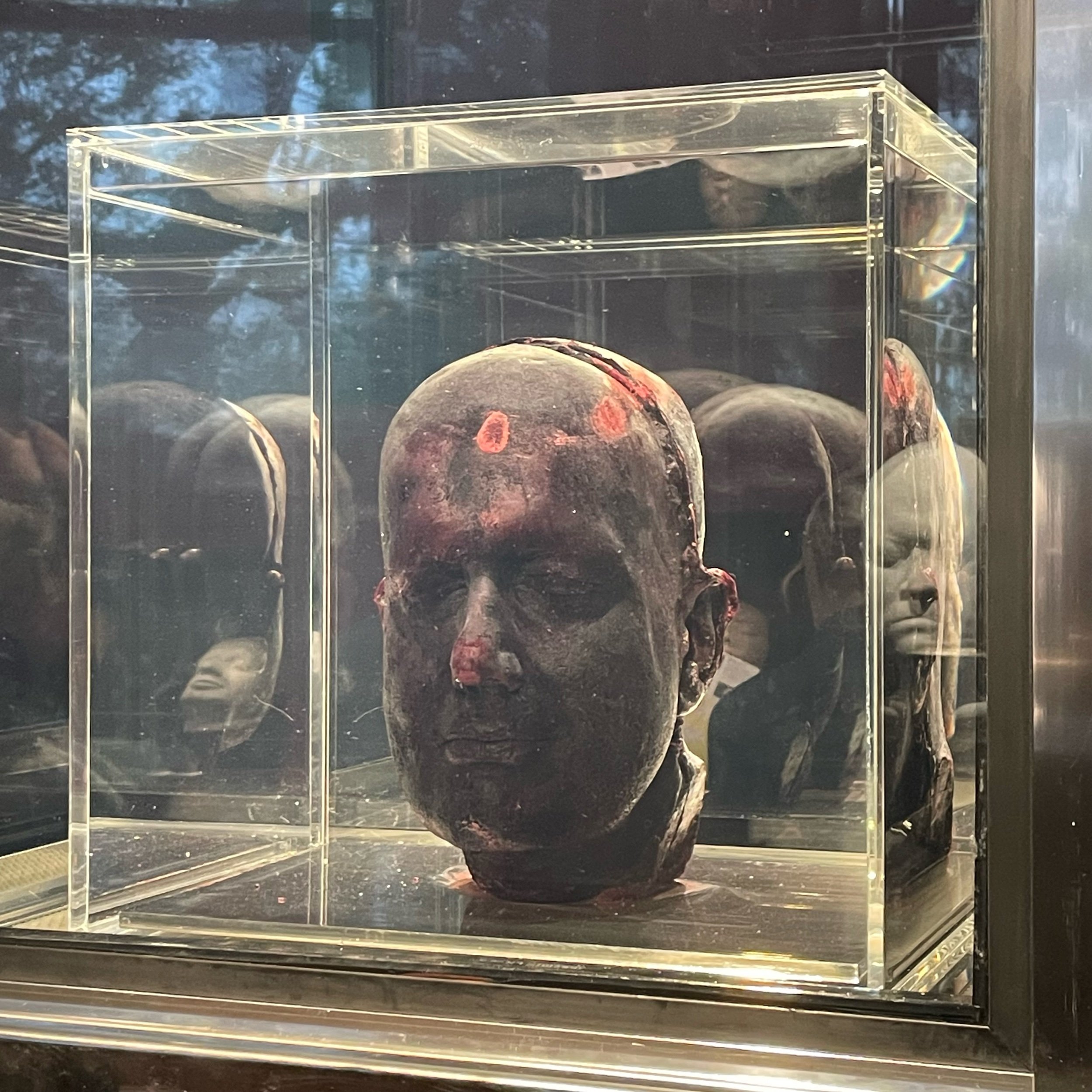

Self (2006)

Marc Quinn (b.1964)

Self, 2006

Blood (artist's), liquid silicone, stainless steel, glass, perspex and refrigeration equipment

205 cm x 65 cm x 65 cm

National Portrait Gallery

In 1999 the ‘Sensation’ show landed in Brooklyn, NY bringing with it plenty of now iconic works from the Young British Artists (YBAs) that still cause just as much controversy as they did a quarter century ago. Tracy Emin’s bed. Damien Hirst’s shark. Marcus Harvey‘s painting of Moors murderer Myra Hindley composed from children’s handprints. Chris Ofili’s elephant dung Virgin Mary. Rudy Guiliani, who was mayor of NYC at the time, referred to the show as "sick stuff" and attempted to pull funding for the arts. It’s one of the most influential shows in recent art history and yes, I was there, so I can attest first-hand that the reactions to this show have not been exaggerated. It was evident at the time that I was seeing history being made, but the one piece that had the biggest impact on me and still commands my attention was Self, by Marc Quinn. More commonly referred to as the Blood Head.

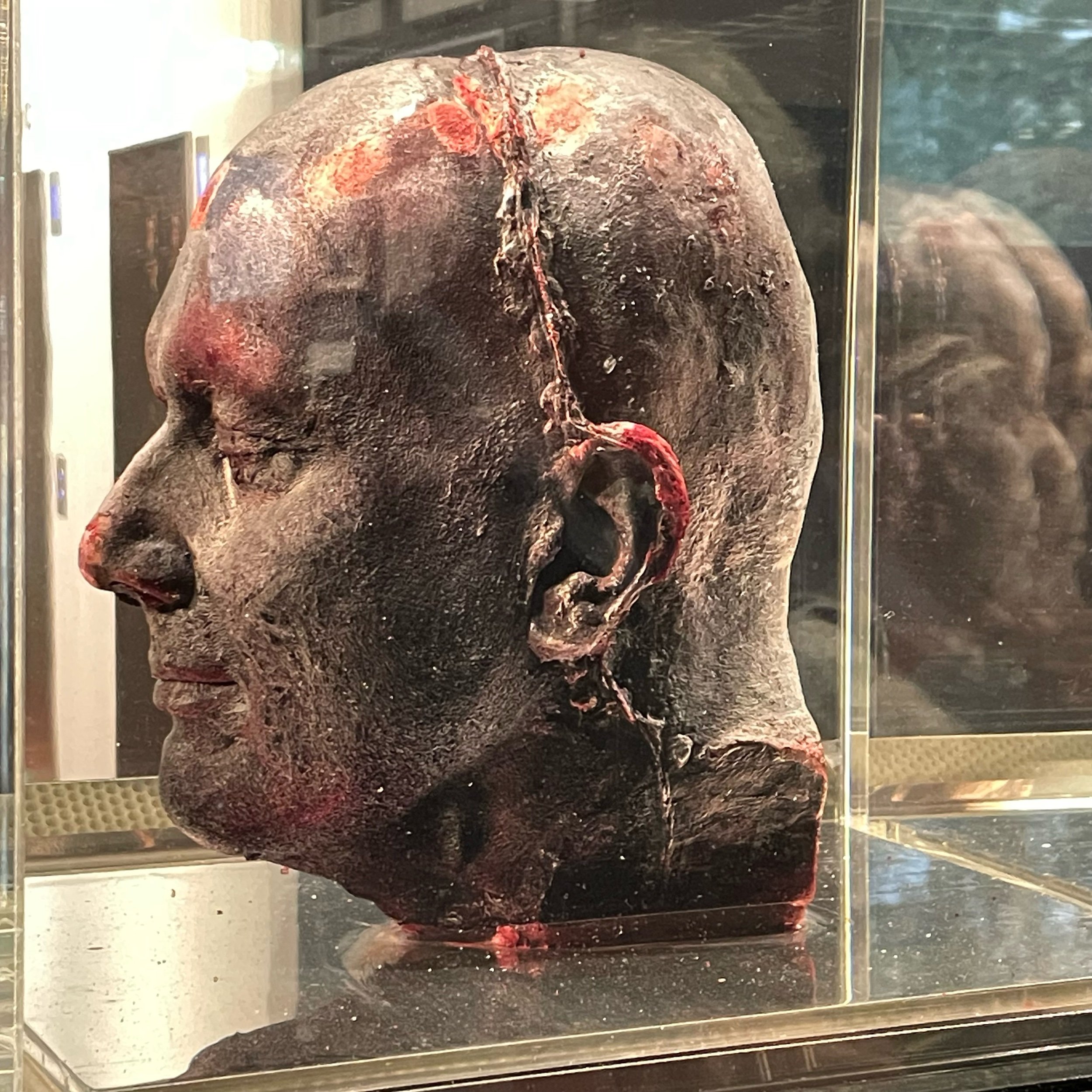

Self is sculpture, but it’s also a vampire popsicle. The artist made a cast of his head which he filled with eight pints of his own blood before being frozen. It is a true self portrait, literally made of the man. And just like the man, it may one day cease to be, as is frequently rumoured to be the case with the original. But even if one were to melt, Quinn creates a new cast every five years as a way to reflect his age and changing face.

The 2006 version is now on display in the recently re-opened National Portrait Gallery. Standing in front of this sculpture is a fascinating and somewhat macabre experience. It’s placed in the centre of a room filled with death masks of famous figures: Oliver Cromwell, John Keats, Aldus Huxley and Francis Bacon to name a few. But Quinn’s head is practically anonymous. The label is somewhat hidden off to the side so most people miss it. They frequently also miss two other revealing clues: the ventilation grills and digital temperature readout on it’s refrigerated plinth.

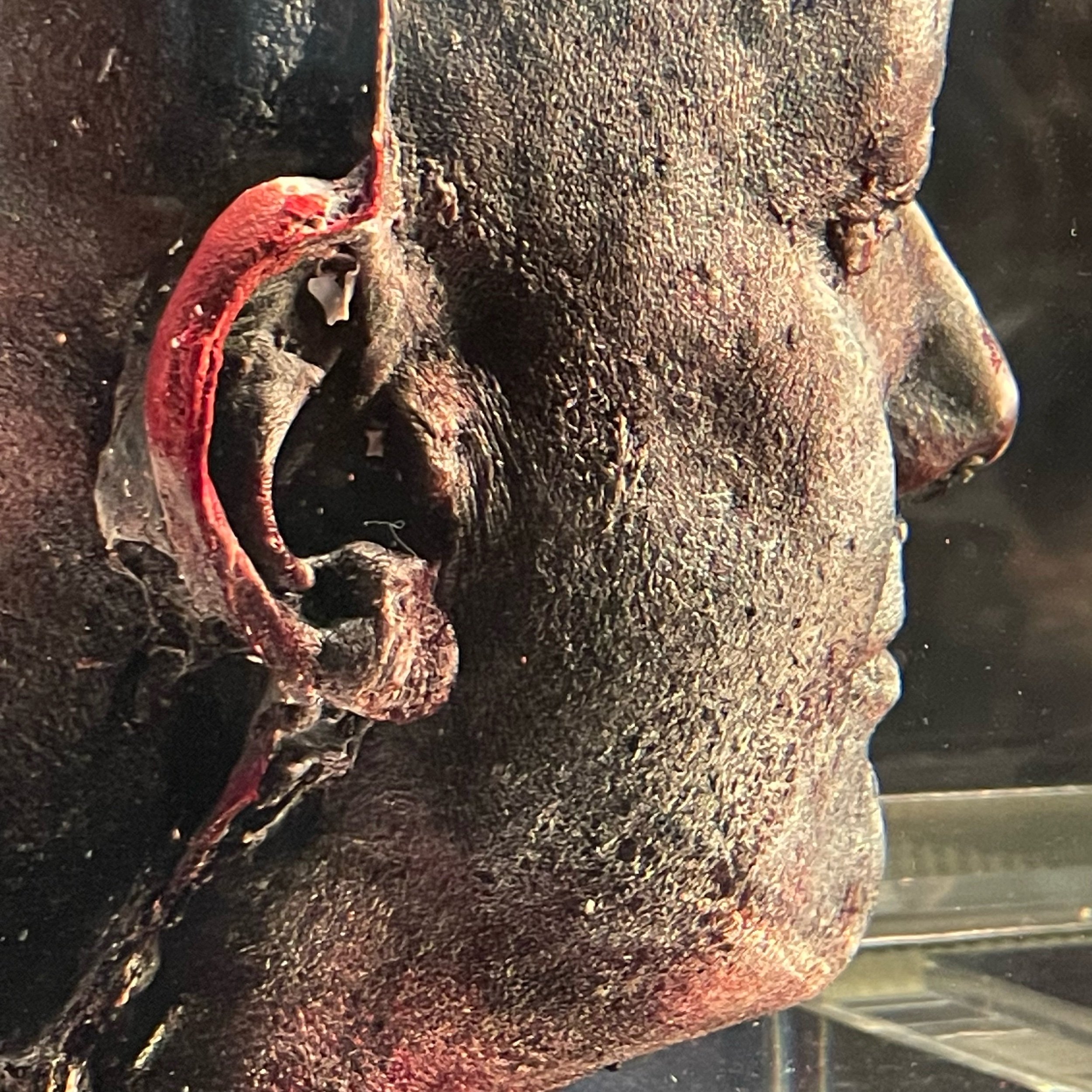

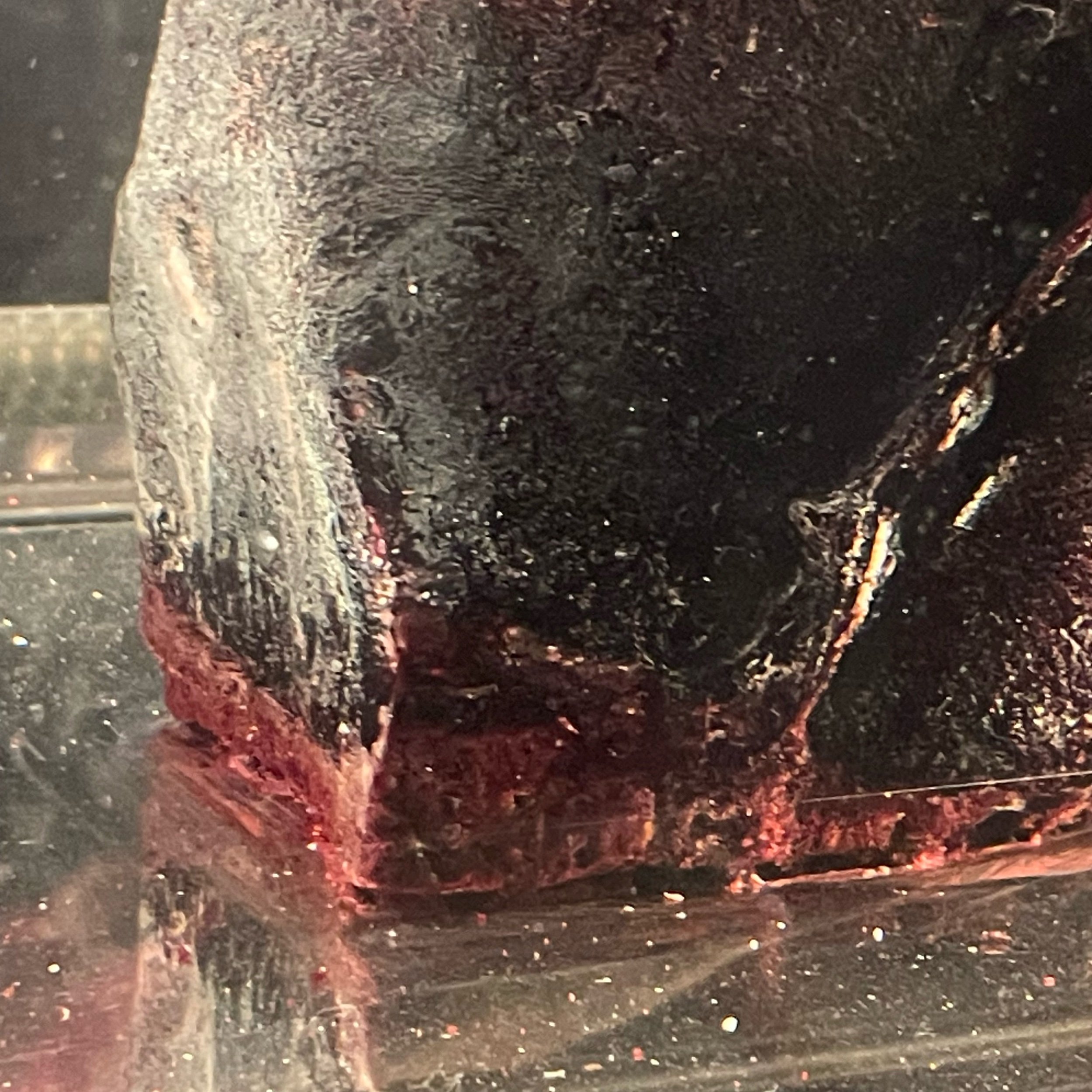

Instead, people stare and wonder who, and what, this dark maroon head encased in perspex actually is. It stands proud on a mirror that’s splattered with red specks, and has a squared off base that looks like a freshly cut slab of butchers meat. It’s amusing to listen to the viewers react:

“It’s probably a plaster cast but… this one looks weird.”

“It’s not his actual head. It’s his blood.”

“Why would they do that?!”

Indeed, that’s the question. Artists have painted with their own blood for centuries, but what Quinn did was something entirely different, giving a subversive new meaning to the concept of ‘sacrifice for your art’. In fact, the volume of blood in the head is roughly equivalent to the amount of blood in an average adult so the collection process must be spread out over a few months. And since Quinn says he’ll repeat the process every five years I guess we can safely assume he doesn’t have hemophobia.

Marc Quinn is 59. If he achieves the average UK male life expectancy then expect at least another four heads to be cast and frozen. Although the last one listed on his website was from 2011, so it’s unclear whether he decided these are no longer worth the effort or maybe his webmaster just needs a good kick up the arse. Regardless, I’m glad that Londoners and visitors, and especially me, once again have the chance to see one of these rare works of art while it’s still frozen in time.

That’s why I like it.

You’re only dancing on this Earth for a short while, and sometimes that includes the art!

Additional reading:

Artist website: marcquinn.com

Artist Instagram: @marcquinnart

Previously, on Why I Like It:

Jul — Red Radish / Scalion (2012), Jen Violette

Jun — Babel (2001), Cildo Meireles

May — Human Frailty (c1656), Salvator Rosa