Clarke Reynolds - The Power of Touch

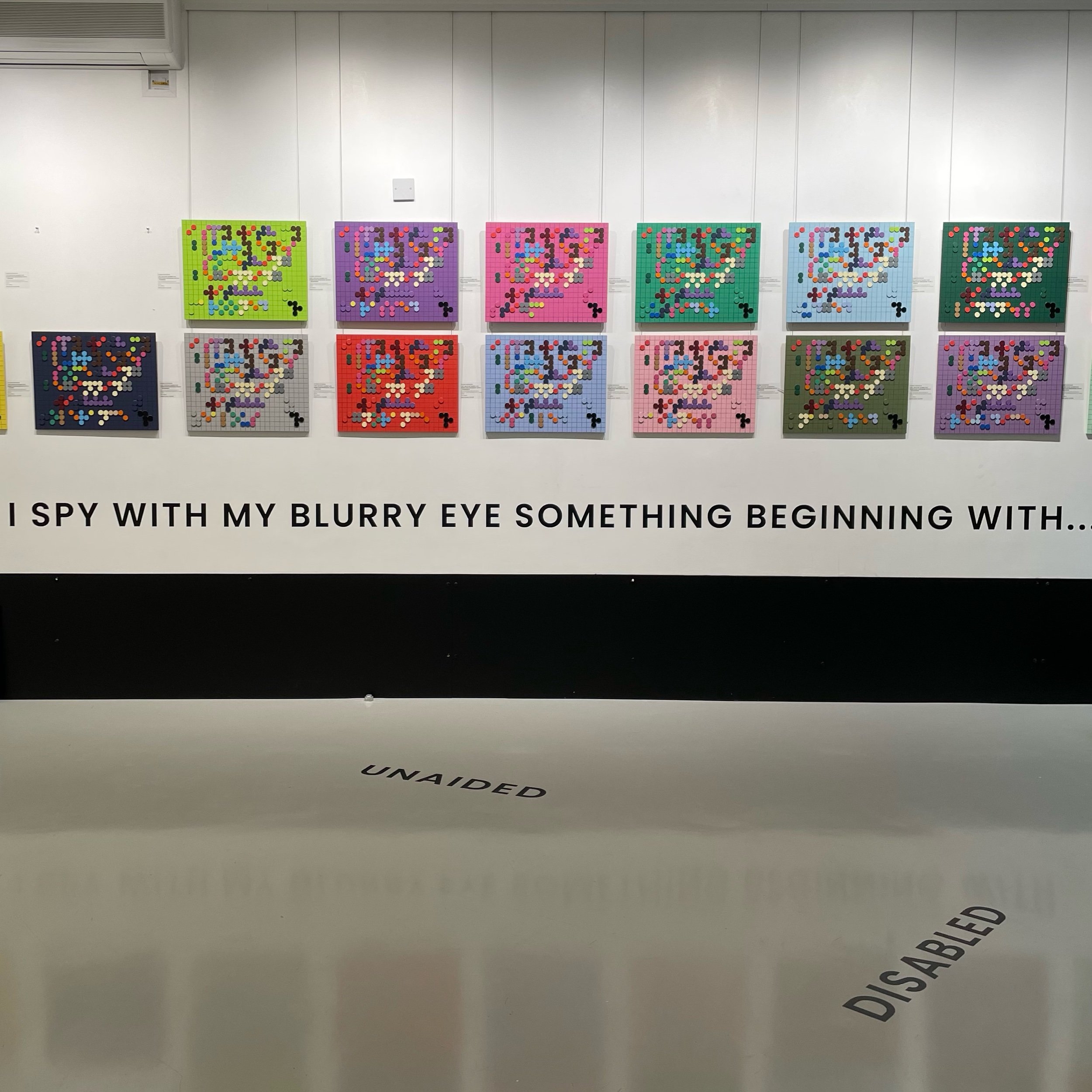

Stare at the dots long enough and maybe you’ll “see” the hidden meanings. Or you can do what I did, and use the colour coded card to decrypt the scripts like a rainy day puzzle. It’s momentarily fun, but daunting to think about doing this for all fifty-plus works. A statement I’m sure will cause the artist to play the world’s smallest violin for me, because he’s blind.

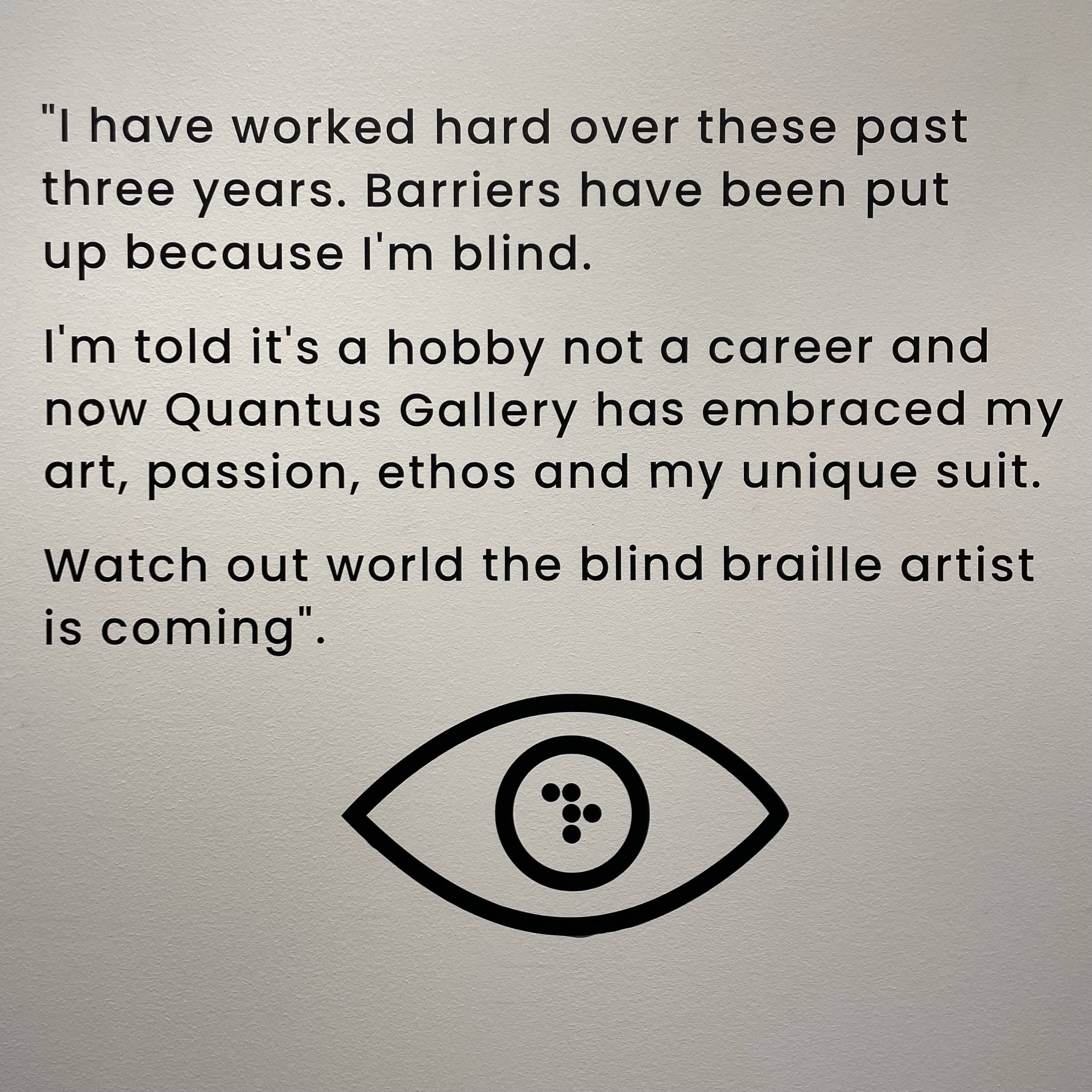

The artist is Clarke Reynolds. He was born with limited sight in his right eye, and began losing sight in his left eye in his 30s. He describes what little sight he has left as “seeing underwater”. One thing Clarke never lost, however, was a passion for art which he’s now turned into his profession. Clarke’s work is clearly rooted in the visual arts, and his approach is to ensure it can be enjoyed by the sighted as well as the blind. His current body of work is based on Braille.

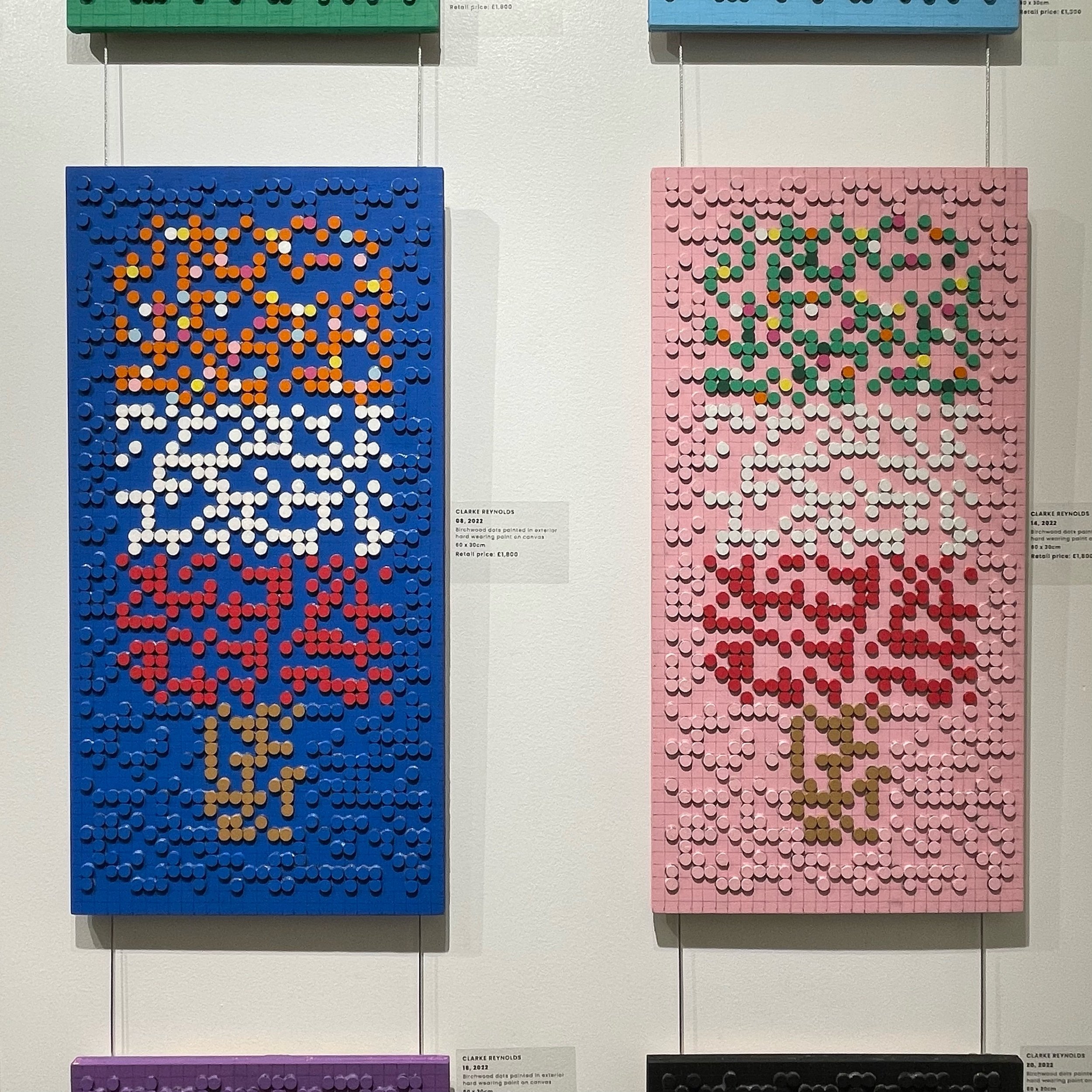

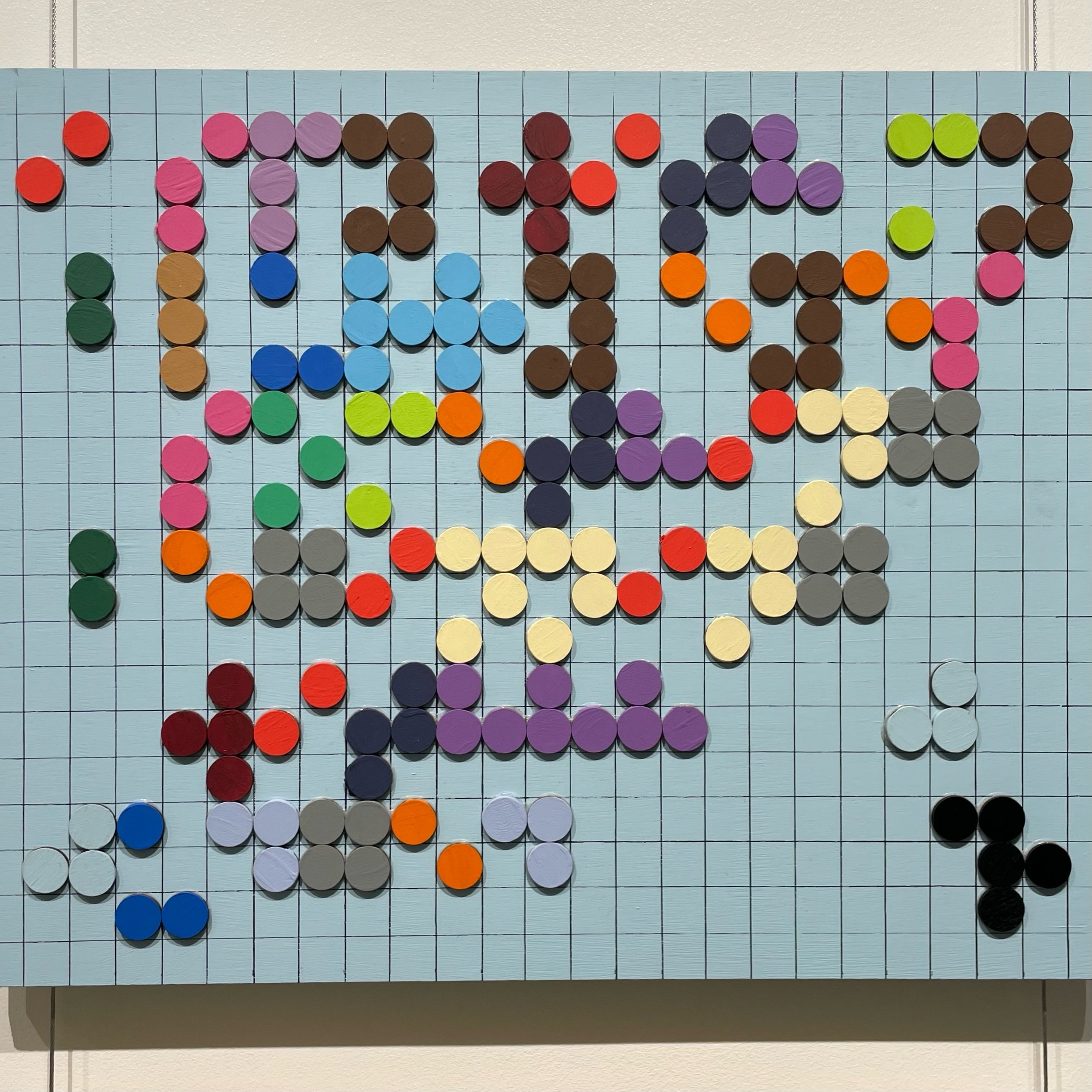

The Braille in Clarke’s art is composed using wooden dots, similar in size but twice as thick as a 10 pence coin, and coated in hard wearing paint. You can touch them and you’re encouraged to. It is, after all, Braille, which plays an important role in the work even though you don’t need to know that to enjoy them. As visual artworks they’re incredibly pleasing to the eye.

The work is evocative of pop art. Brightly coloured dots in a pleasant arrangement. Except anyone who ends up owning one is going to get a massive kick out of being able to explain to their guests that, yes, this “abstract” actually has an answer to that age old art question: “what is it?”

The “it” are words and phrases that act as paintbrushes in many of the pieces, creating seemingly abstract patterns as a result of the 26 colours Clarke’s assigned to the alphabet. I translated one titled Journey which contained the phrase: “It can refer to a persons experience of changing or developing like losing your sight”

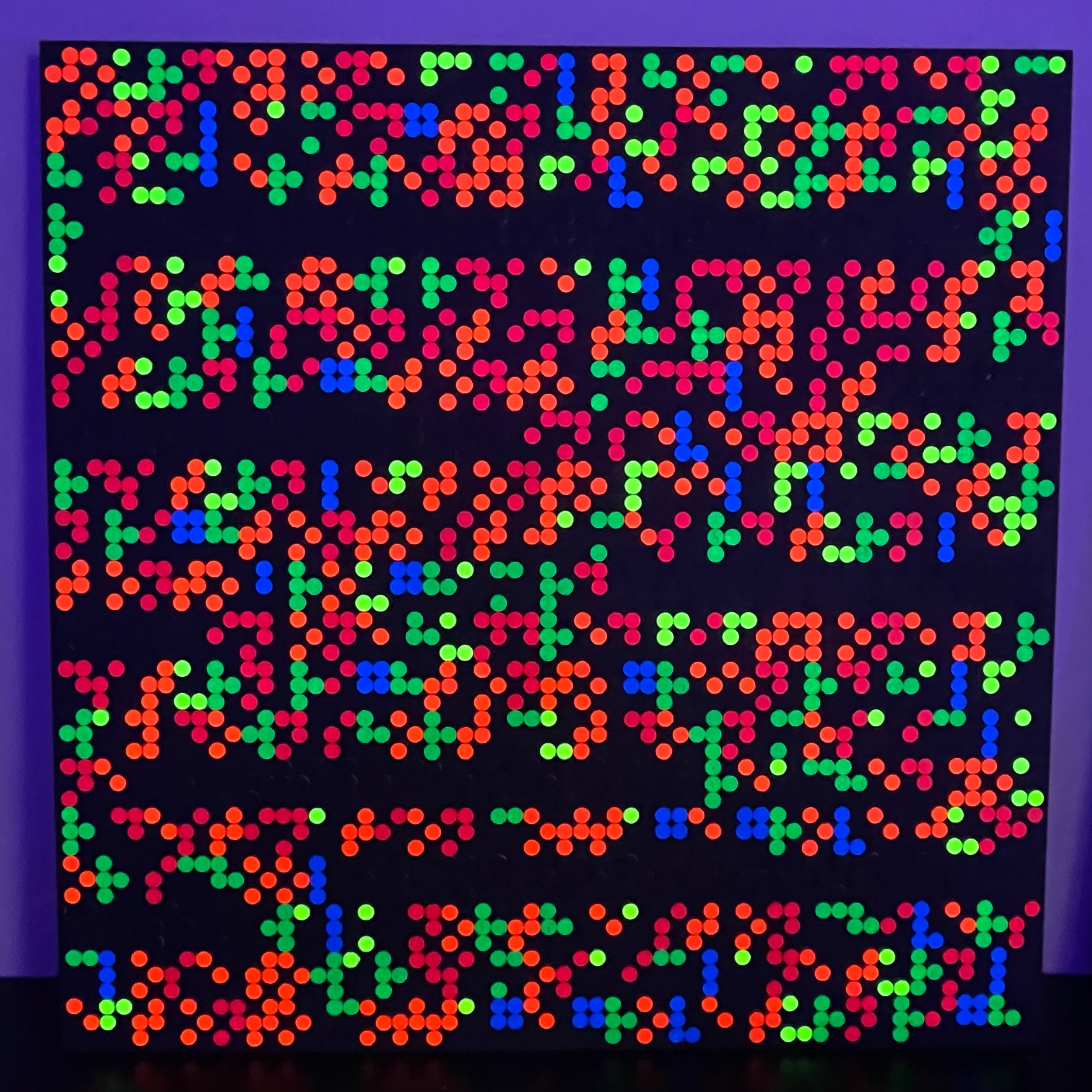

Some boards have a more intentioned approach visually, colouring clusters of dots so that patterns appear like a three-flavoured ice lolly. There are also sitting stools so you can feel the Braille with your butt (probably not the most efficient way to read it) and a darkened room where UV light makes the dots glow bright while you sit and listen to Clarke narrate stories about his personal journey.

I’ve seen and experienced art made by or for those without sight, but can’t recall having ever come across work that was so intentionally accessible to everyone regardless of their abilities and without feeling pandering. Good art should resonate on many levels, and these incredibly pleasing works have just the right balance of visuals, text and touch. It will be exciting to follow Clarke as he continues to push and evolve his practice.

At Quantus Gallery (@quantusgallery) until 04 Feb

Visit seeingwithoutseeing.com and follow @blind.braille.artist on Instagram for more information about the artist.