Do Ho Suh @ Tate Modern

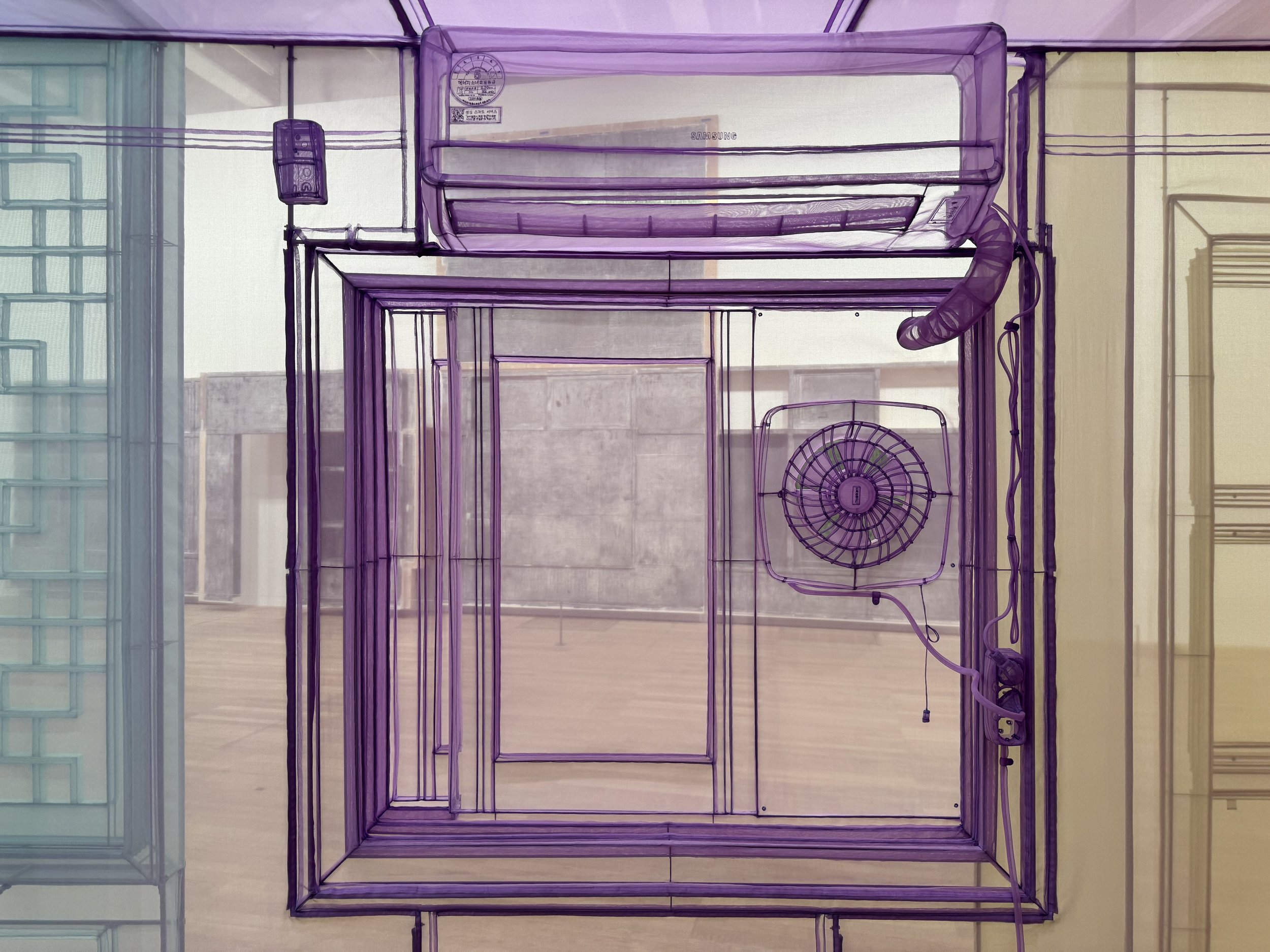

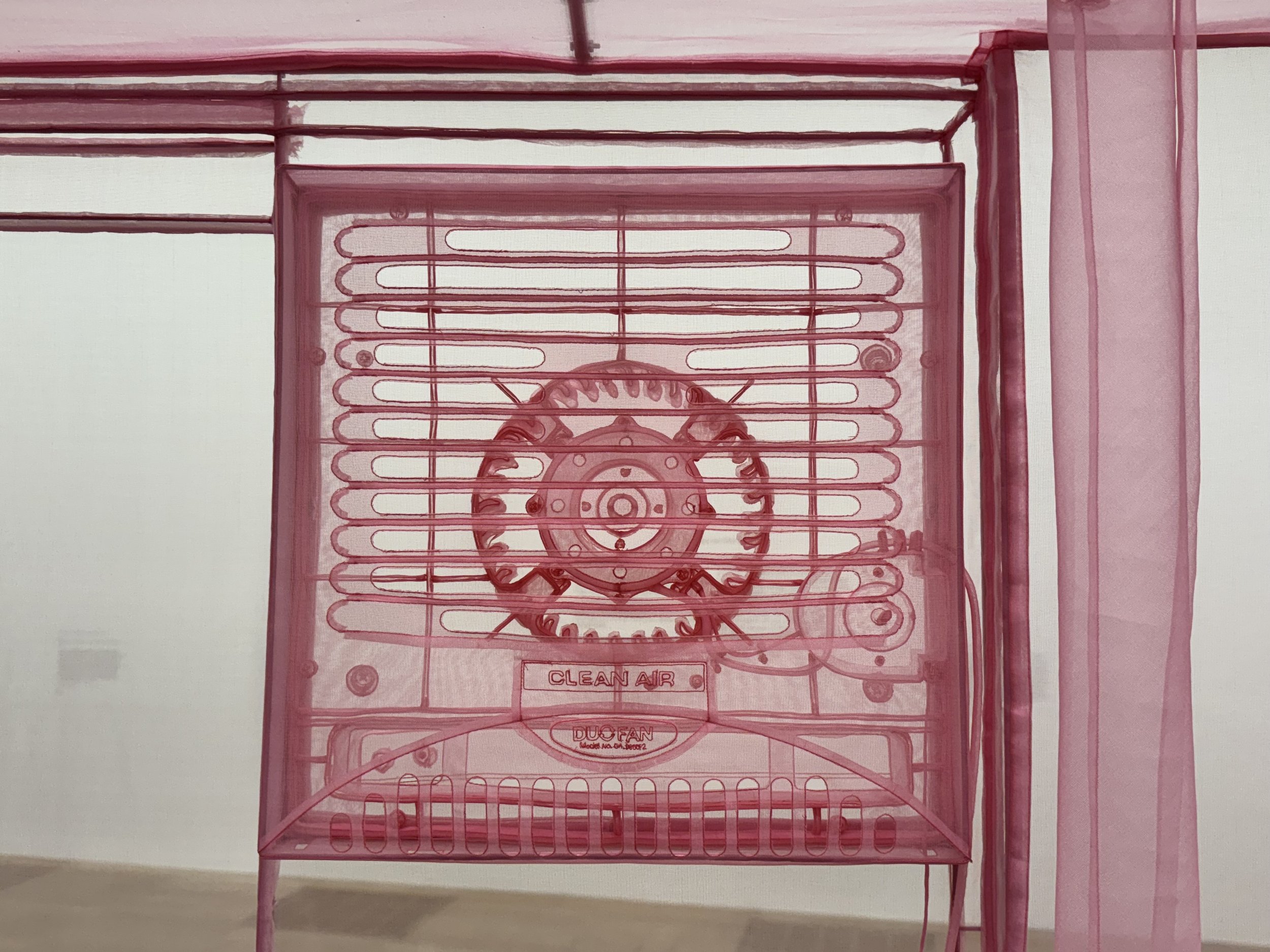

Viewing Walk the House at Tate Modern is a bit like attending a Leicester Square movie premiere. There’s a lot of interesting people in the audience but you’re unlikely to notice them because your focus will be on the A-Listers walking the red carpet. That’s understandable because Do Ho Suh’s life-sized recreations of architectural elements, created by wrapping colourful polyester fabric around metal frames, are so visually appealing and distinctly unique that they are familiar even to those that don’t know the artist’s name.

The works are Suh’s attempts to capture the places he has lived and the things within them. He refers to them as ‘fabric architectures’ but because they’re semi-transparent it feels more appropriate to refer to them as ghostly memories. Memories of walls and skirting boards, door handles and locks, light switches and plugs and anything else you might find that physically defines, and is attached to, the inside of your home. They have an instantly recognisable style and are visually stunning works of art, but they’re a bit of a one-trick pony.

Suh’s artistic practice is rooted around ideas of home, and in the case of his own, he’s spent a lifetime trying to retain and capture every door jamb, wall socket, air vent and architrave he’s lived with. Doing that with colourful fabrics is infinitely more stimulating than a photo, but aside from communicating size and volume the three-dimensional works don’t do much more than remind viewers to notice tiny details within their own home. I love them and they’re beautiful, but that’s really all they do. They aren’t intended to trigger emotion or intellectual rigour. They are Suh’s personal struggle to capture and retain the physicality of his lived experience.

If you want to know what Suh really thinks about the home you need to turn your back on the big installations and study your way around the walls. Large works that look like drawings are actually thread embedded in paper, depicting homes as safety nets and containers of complexity. Actual drawings and watercolours depict homes with legs, or as monsters about to eat each other. Video works of the furnishings and people that once inhabited failed housing estates remind us that sanctuaries don’t need to be outwardly beautiful in order to have comfort and character. These other series of work provide a much greater insight into Suh’s mindset, and they had me thinking a lot more deeply about the concept of ‘home’ than his ghostly memories.

Alas, there’s only a scattering of those works. Their inclusion hints at a wider body of art that might one day be worthy of a proper retrospective, but since everything is displayed in one large room — an awe-inspiring reminder of the vast and cavernous spaces created in the 2016 Tate Modern expansion — it’s hard to focus on them because of the three giant stars of the show vying for your attention.

One of those A-listers is Rubbing/Loving: Seoul Home, a life-sized replica of his childhood hanok house. Suh wrapped his home in mulberry paper, rubbed it with graphite, and left it for nine months to quite literally soak up the elements and atmosphere of and around the structure. Even from up close it’s hard to believe that the entire thing is paper. It has a visual heft you don’t get from the ghostly remnants of physical space in the “perfect room” room. Filled with hundreds of doorknobs, light switches and wall plugs, the space is a jumbled mess that seems to haphazardly catalog every single wall-based utility Suh has come across in his lifetime.

There is a logic to the room explained in the exhibit, but I’m still confused about the meaning. I start contemplating how many doorknobs I’ll turn in my lifetime, a mental exercise that feels more like quirky trivia than deep meditation. The chaotic overload is numbing. There’s a fine line between impressive and obsessive and when an artist repeats an impactful visual effect over and over and over again you begin to question if all meaning has been lost in the artist’s relentless attempts to work something out in his head.

Which brings us to the star of the show: Nest/s, a series of in-between spaces from four different homes Suh has lived in. Stitched together as one long hallway, it’s huge and impressive and Tate could have charged a separate entry fee to capitalise on the social media influencers flocking to take selfies of themselves inside it, because inside it is where you want to be. The transparent fabric architecture surrounds you without obliterating your sight lines, views or even sounds from the rest of the room. It’s a bit like an augmented reality experience, positioning you in two places at once, but not really in either. It makes me think about how much of my time at home is spent ‘elsewhere’, escaping into a novel or a movie or even a board game. In those moments the walls and light switches recede from active views, but I know they’ll always be there when I need them again. There’s a comfort in knowing how to locate a light switch in the dark, and I understand why Suh has spent a lifetime trying to capture that.

Plan your visit

‘Walk the House’ runs until 19 October 2025.

Tickets from £20 adult / discounts available / children under 12 free

Visit tate.org.uk and follow @tate on Instagram for more info about the venue.

Visit the Do Ho Suh Wikipedia page and follow @dohosuhstudio on Instagram for more info about the artist.

Want more London art news and reviews?

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. It’s FREE!