Patchwork of the Century (1951)

Lilian Dring (1908-1998)

Patchwork of the Century (1951)

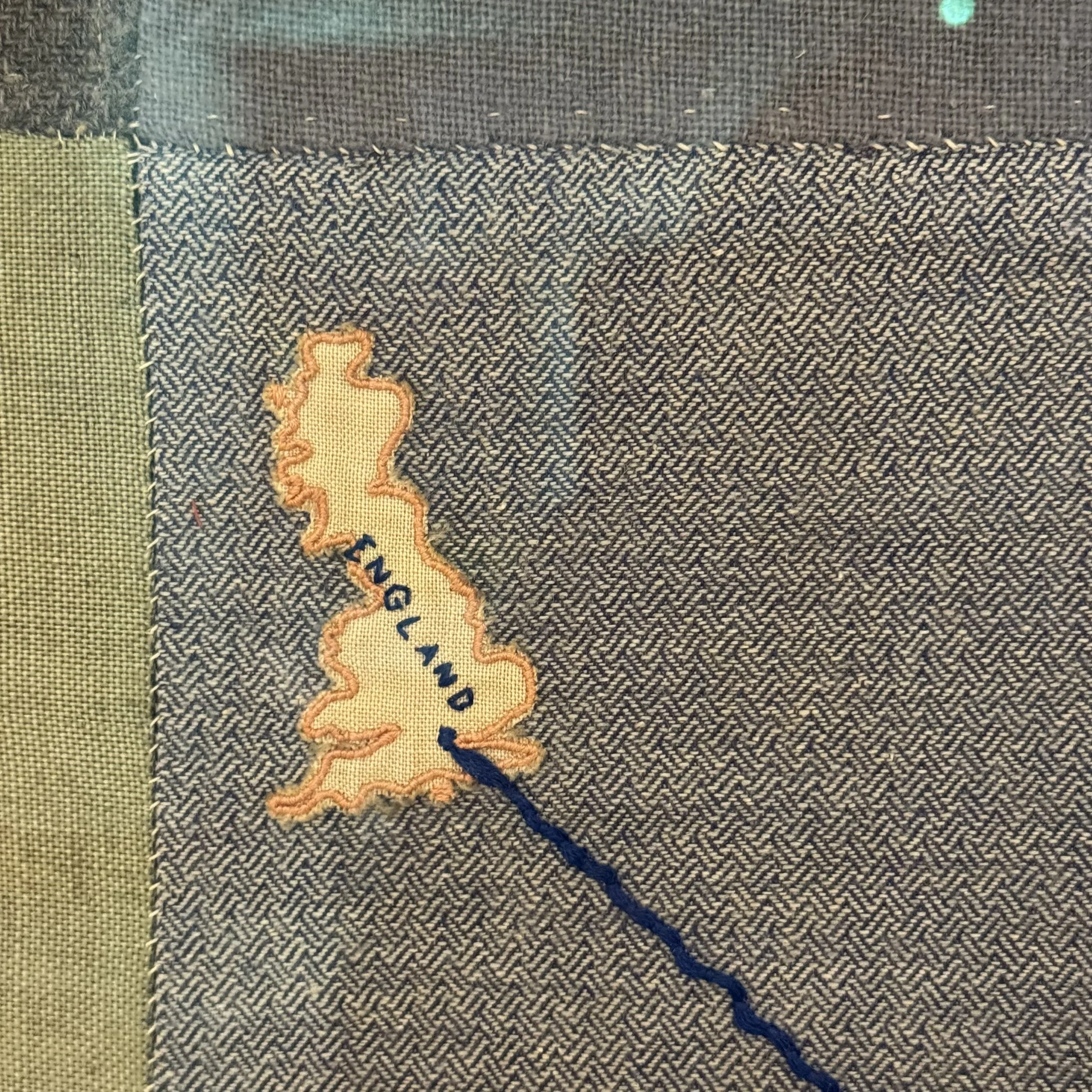

Embroidery and appliqué

300 x 300 cm

Southbank Centre

I’ve been meaning to write about this artwork for over a year but I kept forgetting about it, which is fitting considering how many people walk right past it every day. That’s because it’s quietly hanging on a column located between two things at the Southbank Centre that typically command more urgent visitor focus: the toilets and the ticket/info desk. But every so often it manages to catch someone’s eye, and those who stop to study it are rewarded with one hundred hand sewn images to occupy their time.

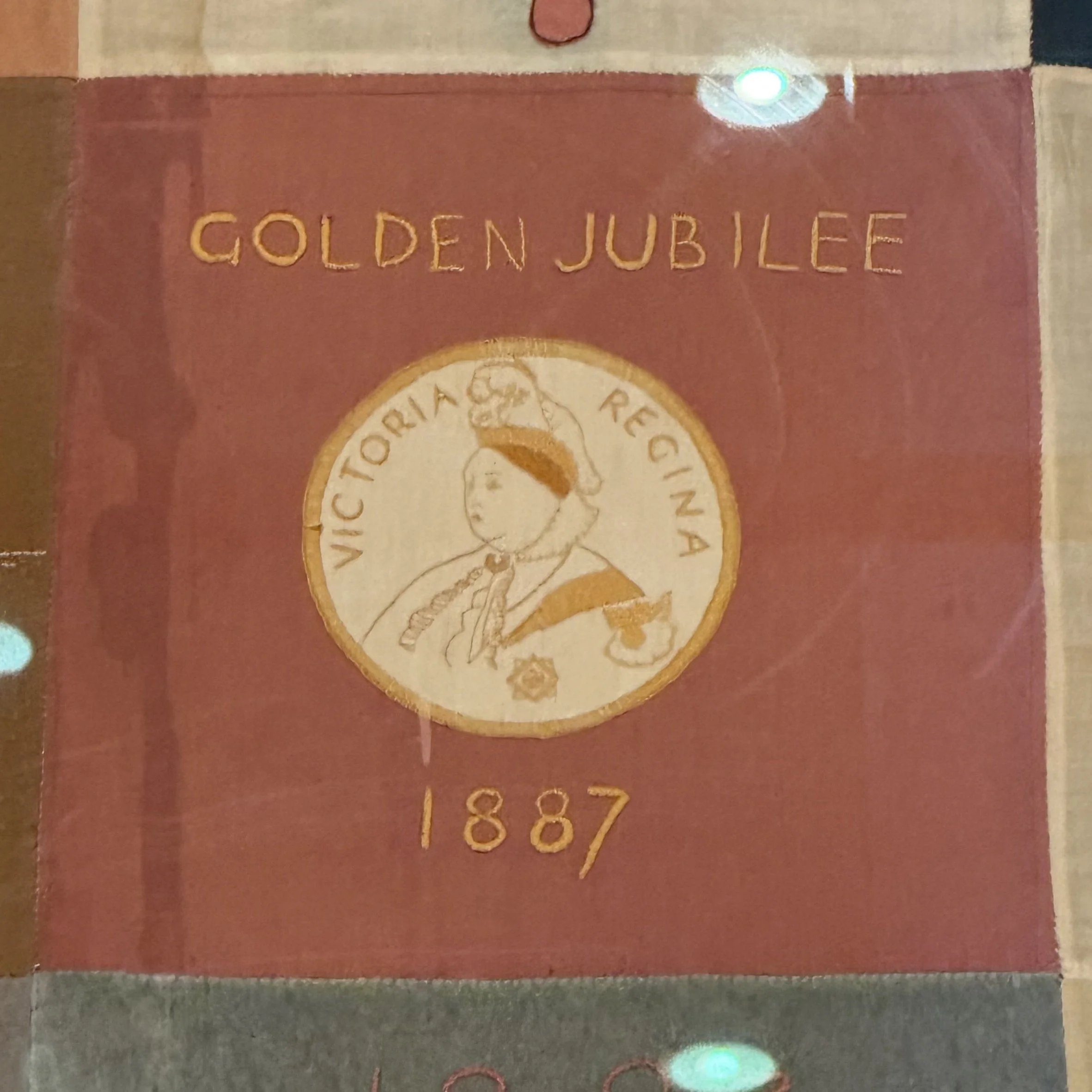

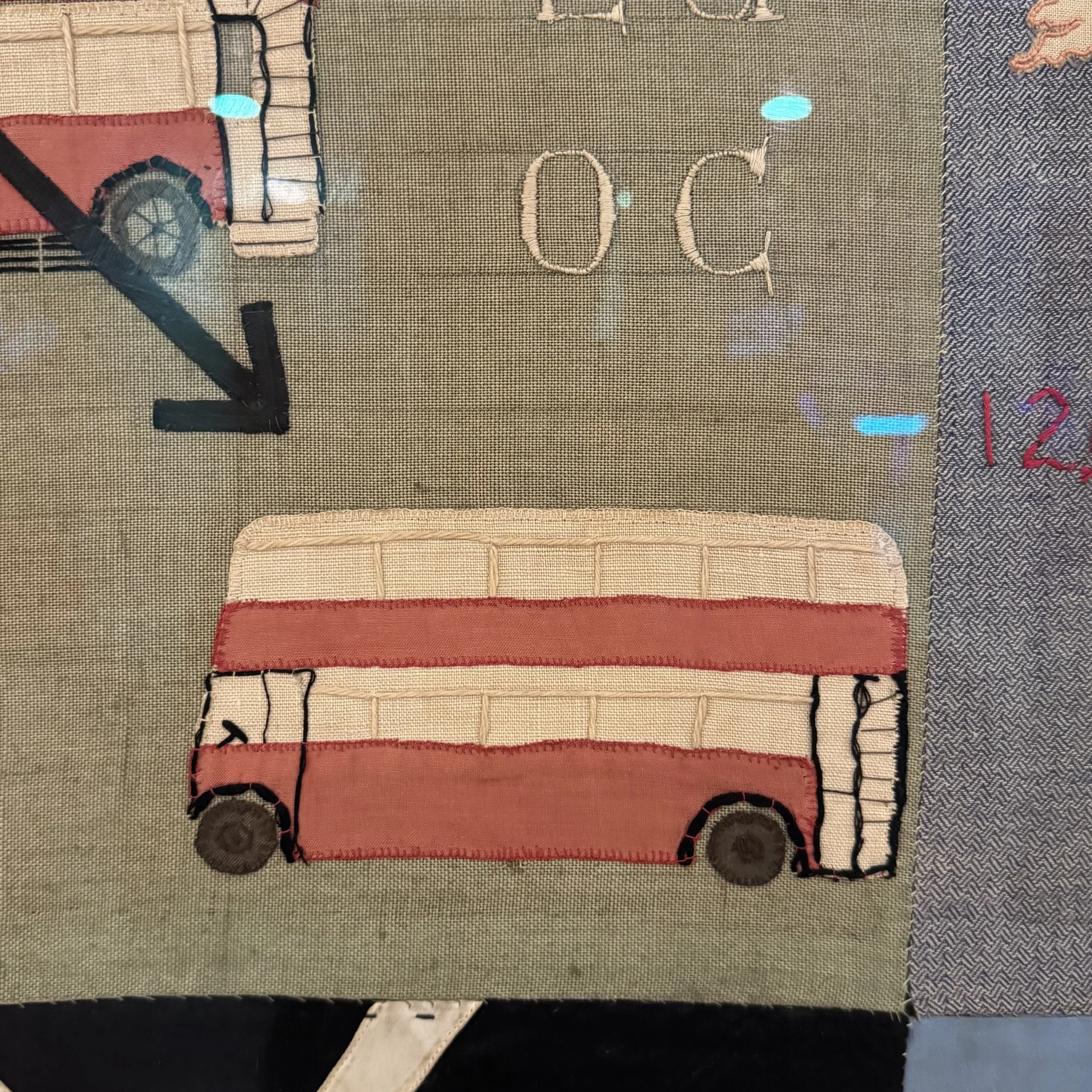

Including a Remington typewriter, a WWI tank and a “mail-cart” bassinet, a precursor to the modern pram, the 100 squares on the Patchwork of the Century represent major milestones, one per year, commencing with the 1851 Great Exhibition that kicks off the grid and ending with the 1950 Festival of Britain, where this quilt once prominently hung. It was originally made for a parallel Women of the Century exhibition, and June Hill’s 2023 article in Embroidery Magazine does a fantastic job of tracing it’s origin and circuitous route to the Southbank Centre should you want to know more.

The artist of the work is Lilian Dring, though I prefer to refer to her as it’s architect. Dring enlisted 80 women to help sew the squares, many of whom were new to needlework. I can’t find any information that confirms how the events, people and technological achievements were selected but I like to imagine Dring and the women formed a small committee to debate not just what should make the cut, but who got to sew each one. I doubt anyone who worked on the quilt in 1950 was alive for the 1851 Great Exhibition, but it’s not that far fetched to assume most of the squares would have been allocated to someone with lived experience of the scene they were given.

One of the reasons many people walk right by is because the visuals appear dim. I assumed it has simply faded as a result of age but a closer look, or a quick read of the wall text, reveals that the patches are made from scraps of old uniforms, tablecloths and blackout fabric. It’s a practical carry-over of the post-war Make Do and Mend mentality that creates a thematic cohesiveness to something that easily could have looked like a jumbled mess. Then again, random juxtapositions in colour, pattern and style are part of what makes quilts so charming.

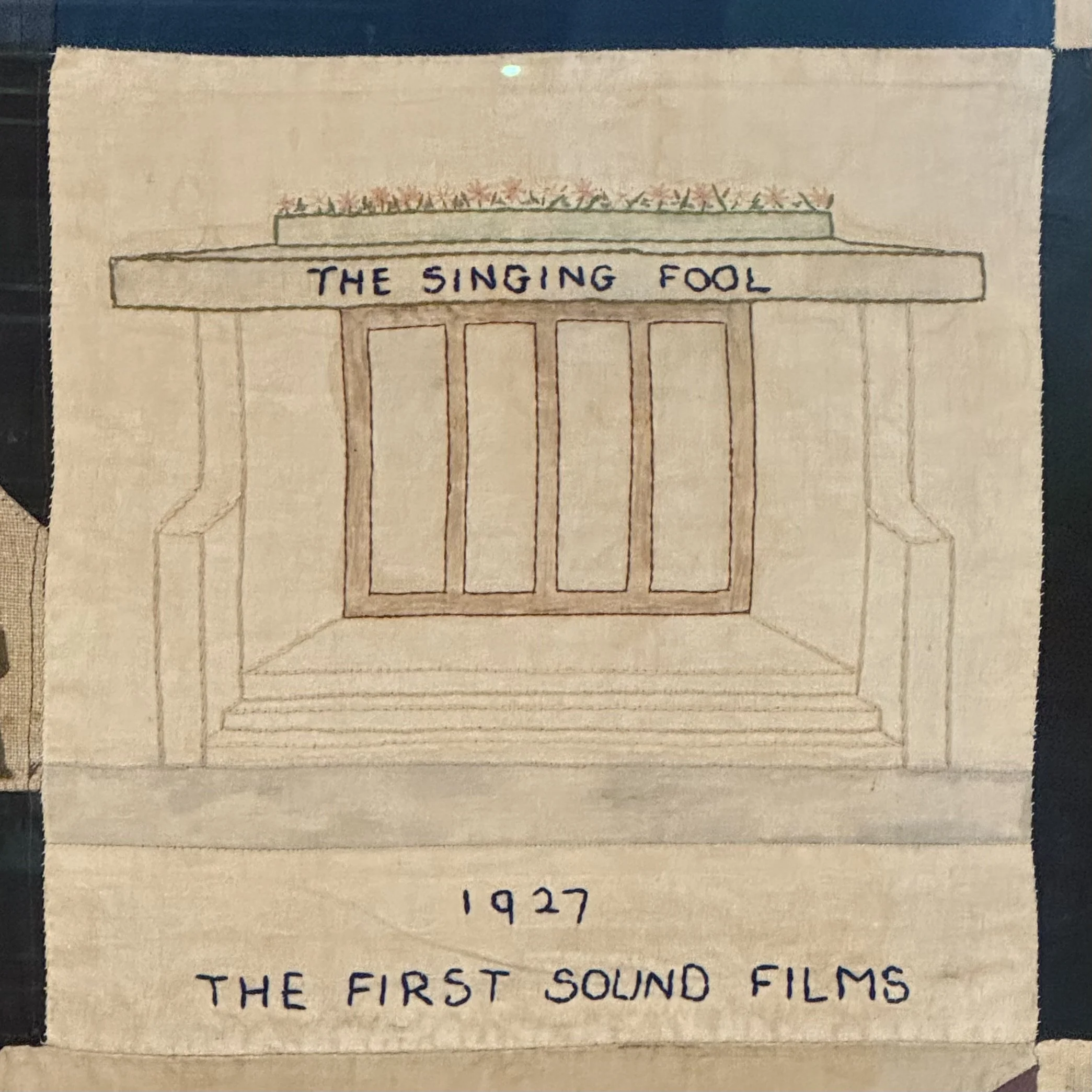

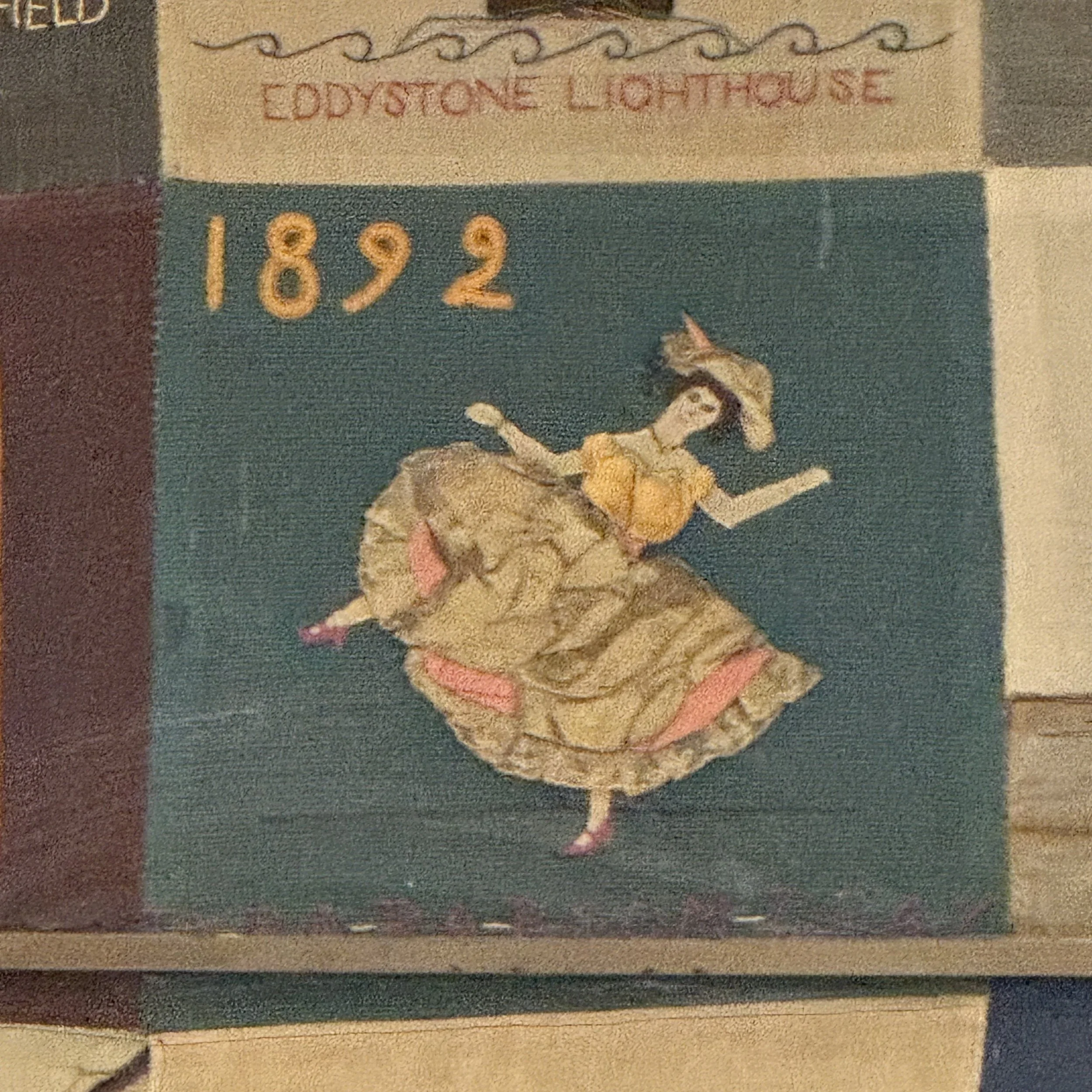

The Patchwork of the Century squares (1851-1950) neatly align with the Machine Age, so it’s unsurprising that many celebrate such miraculous advancements like the first British Steam Locomotive (1874), the opening of the Underground (1900), and the first sound films (1927). A modest nine squares are dedicated to the monarchy but the board isn’t just British. Notable non-war international events include the completion of the Suez Canal (1870), production of the first Ford car (1893) and the Wright Brothers first flight (1903). If you ask nicely the Info Desk will provide you with a handout that explains each of the images, but scanning the grid I’m amazed at how readily recognisable almost everything is, including the four pop culture references. I doubt there are many people alive that still know the steps to The Charleston (1925) but the allocation of the 1865 square to Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland was a wise (or lucky?) choice as it’s still widely enjoyed today.

Monuments and memorials are an important genre of art, but their ability to laser focus your attention on one specific person or event can be both a benefit and a disservice. That’s one of the reasons why I like the Patchwork of the Century. It provides a wide spectrum of teachable moments and poignant memories from a period in history that witnessed momentous change. And unlike the quite literal cold touch of a bronze statue, the fabric and string of this quilt creates a warmth that humanises the births, deaths and relentless march of technological advancements depicted.

Which brings me to another reason why I like it, and yes, I’m stereotyping again, but I don’t care: quilts remind me of safety and hugs. The childhood kind I got from my grandmothers, who’d wrap me up in one of their homemade blankets when I would fall asleep on their sofa. A quilt, by definition, is something functional. But they are also traditionally home- and hand-made so being wrapped up in one feels, quite literally, like a proxy for a hug. Quilts envelop you snugly, keeping you safe and warm and feeling loved. Which might be why discussions quickly get contentious should you wish to debate whether they are craft or art but I think Tracy Chevalier makes the best, most passionate case that “art is not defined by how it is made, but by what it does to us”.

Which brings me to the most personally impactful outcome of Dring’s Patchwork: it makes me take stock of my own life. It makes me wonder what person, thing or event I might depict from each of the years I’ve lived, and to ponder about the un-sewn squares that lay ahead.

In twenty five years Dring’s Patchwork will turn 100. I hope, and suppose, a sequel might be sewn. 1951-2050 aligns with the Nuclear, Space and Information Ages so there won’t be a shortage of milestones to choose from, though I suspect the selection of cultural squares could be highly contentious. Then again, in twenty five years time our AI overlords will probably just tell us what the list is, but they’ll still need to rely on a human to hand stitch it.

That’s why I like it.

Every body loves a list.

Previously, on Why I Like It:

Dec — 20:50 (1987), Richard Wilson

Nov — Don’t (2024), Diana Zrnic

Oct — Untitled (Underpainting) (2018), Kerry James Marshall

Want more? Here’s a list of the first three dozen articles in this series.